(This piece is the first in a collection of essays on queer readings of the Metal Gear Solid series, and serves as an introduction of sorts. It begins by exploring the two recurring themes I’ll be covering – compulsory heterosexuality and an active rejection of the queer – before discussing the games’ portrayals of gender and bisexuality, with a particular focus on Strangelove. It contains general series spoilers, but nothing for V outside of Strangelove’s subplot.)

Naked Snake: Strangelove… Is that a code name?

Strangelove: No, just a nickname. […] Back when I was at ARPA, I kept a photo of The Boss on my desk. I was totally engrossed in my research and showed no interest in the opposite sex, plus I had a photo of a woman on my desk… The fools around me turned it into a cruel taunt, calling me “Strangelove”. […] in their eyes homosexuality was something strange. They were incapable of seeing things outside the lens of their own standards.

– Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker

*

The Metal Gear Solid games get a lot of praise for telling ambitious, cinematic stories with memorable characters and strong themes, even if they don’t always stick the landing. But they also cop a lot of flak for the less-than-elegant way they handle a lot of things, chief among them gender politics, and justifiably so. There’s been a lot of discussion around the way the series handles its women – just look at the uproar about Quiet – but this feels like a reductive approach which misses out on a lot of really interesting potential for analysis. I think the series deserves to be looked at through a broader lens, one which encompasses sexuality as well as gender and looks at more than just the obvious female characters.

I’d put forward the basic framework that MGS’s sexual politics operate on two different but connected levels. First, it assigns its heroes a compulsory heterosexuality, intended to prove their masculinity by giving them relationships with women. No matter how tacked-on or unconvincing the romance plot, the hero must get the girl; otherwise, this opens them up to all sorts of queer and “unmasculine” possibilities. This is complicated somewhat in later titles, but by and large the pattern stands. Secondly, whenever the series actually considers these possibilities, it shuts them down as quickly as it can. Queerness is thus reduced to a punchline, or else deployed as otherness to add another layer of villainy to its enemies, with a single exception in the form of Ocelot. And so, for all its attempts to interrogate masculinity, the series stumbles because it cannot uncouple what it means to be a man from what it means to be a straight one.

But, of course, the issue runs a lot deeper than that.

Let’s get this out of the way right now: basically every MGS antagonist of any significance is either explicitly queer or can be read as such. Liquid is blatantly coded gay, checking just about all the boxes of campy villainy you could care to name. Solidus – and, if you’d like to extend the argument, Zero! – is possessed of a profound non-sexuality which could be read as queer in a broader sense. Volgin’s bisexuality is openly discussed by other characters, and we meet both his male and female lovers. And, while Ocelot is never explicitly confirmed one way or the other, the amount of subtext in support of it is frankly ludicrous. (That said, Ocelot’s ambiguous feelings for Big Boss are also the only queer motif the series handles with respect, but I’ll come to that another time.)

The issue, then, manifests in the way that queerness becomes one of the key trappings of villainy. What purpose does it serve for us to know that Volgin is bisexual, except to underscore his cruelty? Why should we care that Vamp’s codename comes from his sexuality rather than his powers? It becomes reduced to a surface trait, intended to underscore the otherness and wrongness of the enemy.

There are a lot of places I could start with this topic, but I’m interested in the way the series portrays bisexuality for a couple of major reasons. Firstly, nearly all the canonically queer characters in MGS are bisexual, which means it offers the most potential for analysis. Secondly, I myself am bi, which means I have a definite stake in the way these characters are represented. And finally, there’s a sharp divide between the way the series narrativises its male and female bi characters which I think is worth exploring.

Despite the fact there are only a couple of confirmed bisexual male characters, there’s a surprising amount of leeway to interpret the men of Metal Gear as queer. (The first example which springs to mind is Kaz, who plays around with women but has a relationship to Big Boss which goes well beyond homoerotic. And he’s only the most blatant, since a significant number of male characters have ambiguous relationships with other men, including both Solid Snake and Big Boss.) Part of this stems from a genuine desire to complicate and interrogate masculinity, but that’s perhaps giving the writing too much credit. It’s never taken seriously and, whenever these possibilities do come up, they’re dismissed as a joke. Ultimately, there’s a real binary in the way the series handles its queer characters and possibilities: it’s always reduced to either comedy or villainy. Queerness is othered and, by extension, heterosexuality becomes inherently heroic.

Or, as this piece so succinctly puts it:

The problem with Metal Gear Solid, interestingly, comes not from a lack of queer characters, or a lack of positive queer subtext, but from a tension between textual queer villainy and death and subtextual queer love and romance.

(I personally take a far less benevolent standpoint on the intention behind all this subtext, but this is another point I’ll come back to later.)

Across the course of the games, we get precisely two bisexual men of real importance, and they’re both bad guys. One is Vamp, a former American counterterrorist operative who’s a recurring foe in 2 and 4; the other is Volgin, a Soviet GRU colonel and the major antagonist of 3. And there are actually a lot of similarities in their portrayals, none of which are positive. Both men are known for their cruelty, and both pair hypersexuality with masculinity and power. However, the physical prowess that comes with this is framed as distinctly inhuman – Vamp has supernatural speed and can’t be killed, while Volgin is hugely strong and can manipulate electricity. These men are therefore emblematic of a destructive, othered masculinity which is shown to run rampant and spill over into every aspect of their lives.

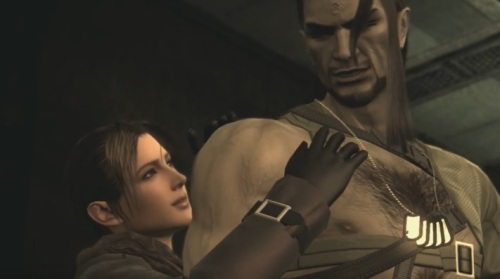

In particular, Volgin is a textbook example of a depraved bisexual, blending sadism with a particularly robust sexuality. He boasts about his wartime achievements, hurts EVA on multiple occasions despite her position as his lover, and avidly enjoys torturing his foes. In addition, there’s a particularly memorable sequence where Snake is sent to infiltrate the compound of Groznyj Grad by posing as the Colonel’s lover, a man named Major Raikov. (I could churn out an essay on Raikov alone, who’s simultaneously one of the series’ worst-written and most interesting characters, but that’s a tangent.) While in disguise, Snake finds himself cornered by Volgin, who manages to figure him out by grabbing his crotch… and realising that’s not his boyfriend’s junk. This moment really typifies his portrayal: he’s a perfect storm of villainy and virility.

The best thing you can say about Vamp, on the other hand, is that some aspects of his portrayal are almost excusable. His hypersexuality has a sense that Volgin’s lacks, at least during his debut in 2, because his blatant virility works in service of a wider theme. Next to Raiden, whose masculinity is contested at every juncture, Vamp is unambiguously manly and the most threatening kind of queer: he’s powerfully built, spends most of the game shirtless, and licks a whole lot of knives. Oh, and by the way, his codename doesn’t come from his powers.

Solid Snake: When he was just a kid, he lost his family to a terrorist bomb that went off in a church they were attending. His body pierced by a crucifix, Vamp was buried under the rubble for two days before he was finally rescued. During those two days, he survived by feeding on the blood of his family to quench his thirst. That was how he acquired a taste for blood…

Raiden: So that’s why they call him “Vamp”…

Solid Snake: No. “Vamp” isn’t for vampire. It’s because he’s bisexual… Rumor has it Vamp was the lover of Scott Dolph, the Marine Commandant who accidentally died two years ago.

In 4, though, he has no such excuse, and his appearance here actually doesn’t add much. Once again he plays the foil to the less-manly lead, the now-geriatric Solid Snake. In addition, Vamp’s overabundant masculinity appears to introduce complications into the relationship between Naomi and Otacon; she disappears, and when we next see her she’s draping herself all over him. It’s not interesting, though, and he really does nothing but live up to his pseudonym. He’s a shallow pre-existing antagonist who’s an easy – and lazy – candidate to play the role of midboss.

In contrast to their male counterparts, however, there’s a lot less room for interpreting the women of Metal Gear as queer. While there’s nothing stopping the player from reading, say, Meryl or Rose or EVA as bi, these interpretations aren’t especially meaningful ones. Women are either romantically linked to men or else rendered completely sterile, both of which combine to make queer interpretations pretty damn thankless.

The futility of reading any of these characters as bisexual is compounded by the fact that they’re not shown to have any meaningful relationships with other women. While the Bechdel Test is hardly the be-all and end-all of feminist criticism, it’s worth noting that most games in the series put up a pretty feeble attempt at passing. In 2, Emma seems to exist largely to have Rose demonstrate her jealousy over her boyfriend, and they never even have it out directly; in 3, EVA and The Boss have one of the most important conversations in the timeline, but it happens entirely offscreen; in V, the only time two female characters talk is when a pair of unnamed Mother Base soldiers discuss the intricacies of “Team Miller” versus “Team Ocelot”. It serves not only to confirm their heterosexuality, but also to establish it as the default and shut out all other interpretations.

The sole queer female character we get is Dr Strangelove, and her portrayal is… well, it’s all over the place. Her debut in Peace Walker establishes her as being almost exclusively interested in women: her defining features are a deep admiration for The Boss and resentment over her death, to the point of having clear and unambiguous lesbian feelings. She later expresses an interest in both Cecile and Paz, but this is pretty uncomfortably written, and she definitely shares the same predatory overtones as her male counterparts. In one of Paz’s diary tapes, she discusses an encounter with Strangelove in which the doctor forcibly applies sunscreen to her; she initially resists, but soon finds herself enjoying the experience. As if the content alone wasn’t bad enough, the writing is reminiscent of cheap erotica, like we’re supposed to be titillated rather than repulsed. (Never mind that we’ve been led to believe Paz is sixteen!) A number of characters refer to her as a lesbian, but I would personally put that down to mistaken assumptions; the ending suggests her future lies with Huey Emmerich, and thus her patterns of attraction make her squarely bisexual.

It’s not that cut-and-dried, though, and V is committed to complicating this in the worst of ways. In the decade since PW, she’s gotten together with Huey and they’ve had a son. (This child is Hal Emmerich, alias Otacon, who becomes a major character later in the timeline.) However, she’s a complete non-presence, having died offscreen a year before the game, and this allows the game total control over her portrayal. Unfortunately, it then uses this power to muddy her intentions, and rewrite her into being a lesbian. Her sole appearance is in voice only, in a ten-minute cassette tape detailing her final moments. Here, she discloses her thoughts and motivations to the spirit of The Boss, preserved within an AI she created:

Strangelove: Me, with child. Can you imagine? I wonder how you took the news. Were you jealous? I knew what I was doing. If I could pass your will on to a child I carried… My genes, your meme… The father would be… irrelevant. If I did that, that child would be ours.

Rather than marrying Huey out of any possible attraction, we’re told that she simply used him in order to have a son. Now, MGS is full of larger-than-life characters who do larger-than-life things, and pretty much every major event in the canon happens because its men have too many feelings. Much of the series backstory centres around an argument between Big Boss and Zero which results in the former leaving the Patriots; Liquid incites the Shadow Moses incident out of anger that his father never acknowledged him; Ocelot spends decades of his life as a multiple agent out of respect for Big Boss and a desire to carry out his will. By the standards of all this, Strangelove’s plot should be nothing unusual.

And yet, I call bullshit. V wants you to believe she’s the kind of person who could set her desires aside and live in a sterile relationship for years. Why? For the sake of a sperm donor, which she admits could have been anyone. (And this is on top of the fact that she seems to demonstrate a pretty explicit interest in Huey in PW which, again, seems like an awful lot of effort to go to in the absence of attraction.) It’s genuinely baffling that V would rather invent a contrived explanation for her actions – solely in order to link Otacon to The Boss’s will! – than allow her to be bi. Perhaps we’re supposed to link her apparent sacrifice here with the absolute “asceticism, renunciation, and self-control” ascribed to The Boss – or perhaps Strangelove herself does – but that explanation feels deeply unsatisfying.

Her brief appearance in V is obsessed with the matter of narrativising her sexuality, even though the way the game constructs her is at clear cross-purposes to her actions. It thus sets up her relationship with Huey as a choice which veers away from her “true” identity and loyalties, which have always lain with The Boss. If you spin out the way this subplot delegitimises bisexuality as an identity, you reach a pretty gross conclusion: Strangelove isn’t “really” bi, she’s a lesbian who made a conscious and temporary decision to go against that. MGS necessarily exists in a state of perpetual rewrite, with each new instalment revising previous canon in all sorts of ways, and V made some awful additions in general. But this is hands-down the worst, and definitely the one I can’t forgive.

Here’s the sad truth of it: Vamp and Volgin’s bisexuality informs their villainy through otherness and unchecked masculinity, but Strangelove’s is reduced to a plot device. It’s bad enough that it operates in service of characters much more important than she is, and she’s relegated to a footnote in the Dark And Manpainy Emmerich Family History. But the narrative doubles down on this because it continues to try and frame her as a lesbian, despite her patterns of attraction. It’s true that Strangelove is just one example of a queer woman, but when she’s also the only example, the burden of representation falls solely to her. This is why diverse casts are important: because the series consistently refuses to entertain the idea that any of the other characters could be anything but straight, the few queer characters we get are universally villains.

The truth is, I don’t even like Strangelove. She has a lot of potential on paper, but the actual execution is lacking, to the point where a lot of things about her portrayal genuinely sicken me. But I’m still furious, because this shit matters. Peace Walker finally gave us a queer character who was amoral rather than evil, a female character who wasn’t tied to a more important man, a woman who actually had some agency over her sexuality, and V promptly threw her under the bus. And literally nobody is talking about this! I suppose it’s because Quiet is such an obvious lightning rod for feminist outrage, but here’s the thing about misogyny: it’s insidious. Having the only female character of any significance walking around naked hurts women, but so does the erasure at play here – and all the more so because there’s a really profound absence of conversation. So let’s open up a dialogue about Strangelove, and about Metal Gear Solid, and about queerness at large. Because I’m fucking sick of this silence, and you should be too.

Pingback: Repost – Critical Distance 2015 in Videogame blogging –

I haven’t played or watched a Let’s Play for these games, but wow what frustrating writing choices- I’d argue that both fans with a lesbian and bisexual interpretation of Strangelove might feel disappointed by the way her interest in men is portrayed, and both interpretations have merit. I mention the lesbian interpretation bc there’s this trend in fiction for lesbian characters to end up with men, and it often expresses messed up attitudes towards bisexual women and lesbians? It seems like there was, at one point, a pretty strong case for Strangelove as a lesbian, before her relationship with a man, so one could argue she was subject to the trope. And it often also results in a lot of friction between people who interpret a given character as bi and people who interpret her as lesbian, because both (rightly) feel their sexuality isn’t treated as legitimate in such narratives.

Also, as you argued a lot of the writing treats her interest in women as predatory, which also sucks for either interpretation.

Seems like there was a character who expressed attraction to both men and women, and it was like, cool, a bisexual lady?! But then the game was like, I don’t think she REALLY could be attracted to men and women :/. And that’s so disappointing.

LikeLike

You’re right – somehow Strangelove’s treatment manages to isolate fans who read her as lesbian as well as bi, which is quite a feat. In general, the more I think about her the more frustrated I become; she’d have been a fantastic character in the hands of just about any other writer, but unfortunately Kojima has a pretty terrible track record with writing women. He does a little better on queer characters – for my money, Ocelot is the best queer character in gaming – but asking him to do a decent job on a woman who’s also queer was probably asking a little much.

LikeLike